WordPress DoSnet

…or how to build your own WordPress-powered denial-of-service network

Pingbacks have been part of the WordPress since the very beginning. One of my previous articles, titled WordPress Pingback Attacks explores two types of denial-of-service attacks that leverage Pingback request processing in WordPress. If you do not know how Pingbacks work, I suggest taking a quick crash-course here.

One of the attacks is a Layer 7, direct denial-of-service attack, performed by a handful of machines targeted at a single WordPress XML-RPC server with pingbacks enabled. Its purpose is to deplete the server of memory resources by forcing it to download and parse a target URL, which is specifically crafted to heighten resource usage while parsing. Up to 6:1 peak-memory-usage-to-download-size ratios have been reliably reproduced. There’s a bug that allows 5 times as much usage (i.e. 30:1 inflation ratios) when setup properly (WordPress 3.4 will suffer from it as well).

The second attack is a Layer 4 (typically bandwidth-exhaustion), reflected distributed denial-of-service attack which utilizes publicly available WordPress sites on servers of any size and is the subject of this article. Buckle up, off we go.

The concept

The scope of the Pingback specification does not define or mention any particular guards for when the target URL is spoofed. WordPress does not “mind” receiving and processing Pingback requests on behalf of a third-party. The WordPress XML-RPC server, under readily-available circumstances, will request absolutely any valid target URL.

WordPress XML-RPC servers worldwide are ready to accept lightweight Pingback XML-RPC payloads (consisting of typically under 2 kilobytes of data; size depends on URL length), reflect them towards a single target, resulting in inflated input-to-output ratios and a denial-of-service attack, that can be distributed among tens of thousands of servers with little effort.

Such reflected/spoofed attacks have been lately heavily used by hacktivist groups to incapacitate some of the largest web resources on the Internet.

Reconnaissance

WordPress is currently deployed in an estimated 5 million instances globally (as per WordPress builtwith trends, and a drastically different 35 million instances reported by Yoast), and is the most-used CMS at the moment. By utilizing a very primitive home-made web spider, a little over 27,000 WordPress instances on different hosts have been added to a database of vulnerable WordPress XML-RPC servers in a matter of 24 hours.

In order to be eligible to “join the fun”, a WordPress installation had to be a WordPress installation (validated against readme.html), have Pingbacks enabled on any one of its pages and thus respond to a fake Pingback XML-RPC request with an expected error.

Among the hundreds of notable WordPress-powered sites that were found to be predisposed to the participation in a DoSnet, belonged to the following domains:

- wired.com

- intel.com

- payoneer.com

- nasa.gov

- stackoverflow.com

- ubuntu.com

- harvard.edu

- house.gov

- census.gov

- senate.gov

- archives.gov

- nationalgeographic.com

- wpmu.org

- edublogs.org blogs and blog.com blogs (I prevented the spider from going to WordPress.com, but that’s vulnerable territory, too)

- mtvu.com

- mashable.com

- trendmicro.com

- 140conf.com

- rsa.com

- …and countless others, including my own blog (not that it’s notable)

I’m sure that many don’t know what Pingbacks are or don’t know that they are active on any of their endpoints. These were among the valid links at the time of exploit.

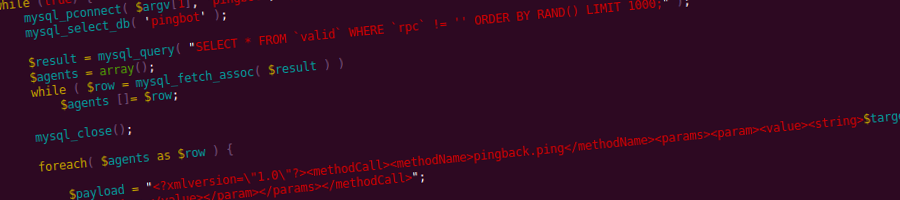

Mounting an attack

Armed with a rather high-quality database (as in low number false positives) of thousands of DoSnet agents (enpoints that are eligible to receive and process requrests), their XML-RPC and Pingback enabled content URLs, a semi-coordinated attack using several cheap boxes can be mounted. Simple PHP worker scripts feeding on agent data, selected at random from one or more databases, is enough.

The target host, has to have a page selected that would inflate to the maximum resource consumption possible, be it bandwidth or memory usage. Large files, dynamic and uncached pages, pages that request other pages, etc. are all good. The attack vector protocol is limited to HTTP(s) GETs. Requests are automatically terminated by the agent after 10 seconds (a hardcoded WordPress setting/guard against long-running requests).

sidenote: since there is, expectedly, no barriers stopping one from targeting any open TCP ports (the schema constraints mean nothing, obviously), turning it into a possible distributed attack at the application level is also possible, in cases where a public service (preferably one that persists a connection for as long as possible) is happy with any sort of data; crafting the request variables of the target URL can even result in all sorts of interesting and valid payloads which are applicable based on targeted remote service.

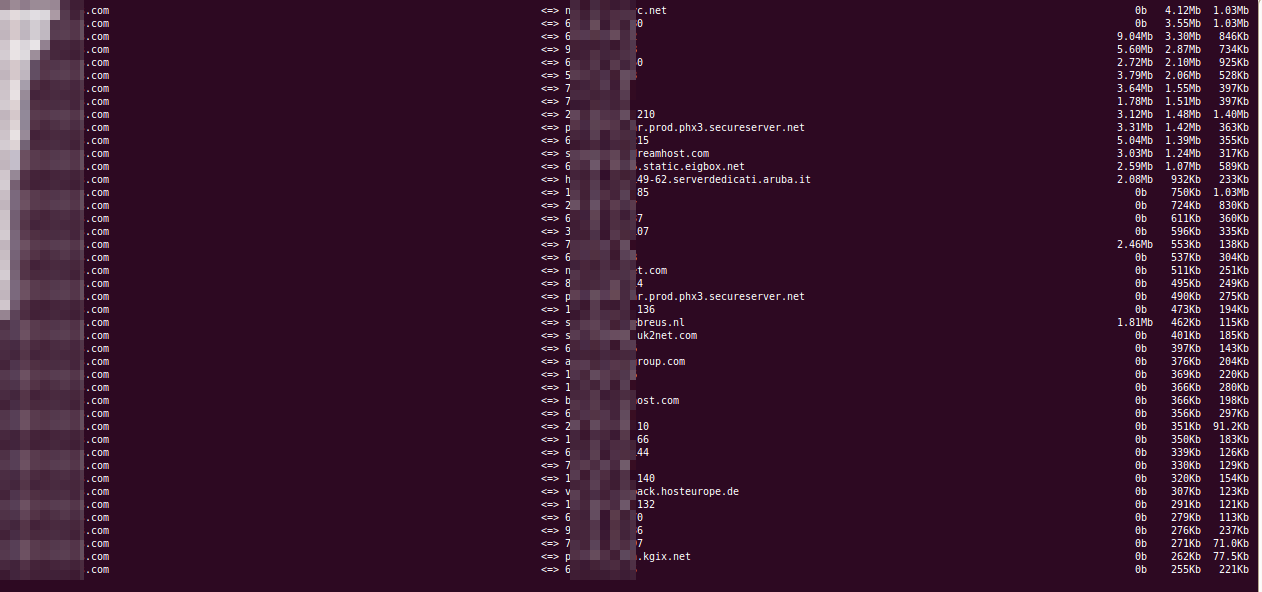

The request dispatchers query the database for several thousand agent records, and start forking themselves creating sockets that merely write and don’t bother to read to minimize traffic on dispatchers. A short delay between forks (~50-100ms) allows for a heavy, sustainable flow that does not overwhelm the Pingback dispatcher resource-wise.

Depending on the target server configuration and the type and size of target content requested, dispatch servers should send at least around 10 requests per second towards a reflecting agent to achieve an intense enough request flow by the agents to clog a typical target.

Proof of concept

A 5MB static file was requested from the target. The target was a dual-core 256MB Xen instance running nginx.

One XML-RPC request dispatcher was used to query a database of 27,000 valid WordPress hosts at random. The target was unable to process requests after several seconds, with over 1300 lingering connections at any single point in time. The dispatcher was a 2GB box.

An aftermath

None of the agents “feel” anything. Requests to an individual agent are rare enough to trigger absolutely nothing. Agent logs will contain access to `xmlrpc.php` and will not usually have access to the contents of the XML-RPC payload. Outgoing connection logs are seldom kept. All appears quiet for WordPress DoSnet agents.

Targets will obviously go down and logs will show IPs belonging to serious organizations around the world. The political side of the vulnerability should raise some concern, many high-profile websites can be forced into a DoSnet and compromised both legally and socially; news of US government allocated IPs attacking kremlin.ru (funny example; not so funny for other country pairs) will spread like wildfire; neither will be too happy, even after it turns out to be a little “misunderstanding” caused by the predisposition of WordPress to “bark up any tree” upon request.

Timeline

- 19th March 2007 – https://secunia.com/advisories/24951/ Secunia advisory released, trac ticket #4137

- 14th March 2012 – my independent discovery and proof of concept mailed to WordPress security team, didn’t stumble upon the old advisories while investigating, sorry

- 17th March 2012 – patches (arguably perfect) for both types of attacks submitted, dismissed; core team representatives consider issue to be of low severity with “nothing [they] can really do about it”, which is arguable, unless I’ve missed something of key importance

- 3rd April 2012 – another report mailed with most of the contents in this article, evoked 2 responses – one pointing toward the 2007 report, and the other one pointing out that I used some incorrect terminology, thank you

Mitigation

Everyone has to disable Pingbacks (trollface). Impossible. None to date. Nothing usable in the core. Pity.

Conclusion

IP addresses and hostnames belonging to serious businesses are logged by the target webserver. Not only will targets be successfully attacked, but may also file abuse complaints against the participants of a DDoS. The attack is very scalable and can be prepared for and mounted in a matter of days without any special software or hardware prerequisites.

The participants of the attack cannot be filtered out via any firewall, since they come from thousands of different hosts from all around the world.

Inflation ratios are sky-high (2kb instruction to download up to 5Mb+ of data), meaning a single machine can potentially block out up to a couple of servers and keep them under constant pressure. With a dozen volunteering XML-RPC payload dispatch boxes – nearly anything can be taken down with enough boxes.

The DoS attack vector is primitive, but it appears to work and can pose a serious threat in today’s aggressive world of hacktivism, information security mania and online warfare. I’m surprised WordPress isn’t yet another convenient and powerful tool.

Almost any Pingback server is vulnerable to some extent, unless it prevents target URL spoofing. This probably includes other content-management systems and web application engines, the investigation of which is out of the scope of this article. Drupal, Joomla, have you looked at your code? Or can attackers add fingerprints for your engines, too?

Stay tuned, I have two more goodies queued up for this weekend and next week.

[…] out the continuation to this article over at WordPress-powered denial-of-service botnet. Tweet !function(d,s,id){var […]

I’d be *very* interested to read the details you sent to the security team. I work with the XML-RPC library quite often, and this is something that should be prevented if at all possible. You have my email via this comment, so feel free to contact me privately. If I can confirm, I’ll see what pressure I can put on the rest of the devs …

Eric, thank you for dropping by, mailed you the minimum source code and the database of 27,000+ valid endpoints (your blog is part of the botnet database as well, valid endpoint is: https://mindsharestrategy.com/2011/how-to-publish-a-wordpress-plugin-subversion), bomb away 😀

Hi, this it GREAT! You are brilliant!! Its there anyway that you could send me the script and details to test it in a virtual enviroment? Have you ever think about presenting this?

Thanks in advance, I expect your email!

Ramon, I’ve dropped some useful files into your inbox, check your mail (same mail you left this comment with).

I have not pursued the issue after being disregarded by the WordPress security team and have not presented this anywhere other than here due to the overall disinterest by the WordPress community and its users, too.

Today, however, I stumbled upon https://blog.cloudflare.com/65gbps-ddos-no-problem which reminded me of the time I gathered a 20k-node botnet in a day or two without breaking a sweat, thanks to WordPress.

In any case, contact me back if you need any other information, glad to have aroused some interest in the issue.

Hi thanks for the email even when I never got the files. Ironically I was refered from (https://blog.cloudflare.com/65gbps-ddos-no-problem) to here, someone in the comments posted the url of this article. I know this is few years old but It was great the way you exposed it, really simple and easy.

Thanks again!

PS: Can you please try to resend the files again?

I believe “the” someone that posted this url in https://blog.cloudflare.com/65gbps-ddos-no-problem was you lol

Hi,

interesting post! Have you also checked some other famous blogging engines if their pingback libs are also vulnerable? Might be interesting..

Is it possible to take a look at the script/poc?

Cheers,

robin

Robin, thank you. I have given the second best Drupal and Joomla engines a thought back when I was exploring this, but had no time to dig any of their code. I suppose they are as vulnerable as WordPress, there is not one simple mass solution to mitigate becoming a bot. There were several attempts at providing patches for WordPress specifically, none of which made the cut. It should be fairly simple to test Joomla and Drupal by sending a Pingback from a machine with a target to another machine and see if it returns a call. The important thing with WordPress is that is downloads the HTML of the page to check for a valid link back, this is what makes the attack successful. If Joomla and Drupal and other CMSes/services with Pingbacks enabled do download the whole page – they are vulnerable. Spidering Joomla and Drupal blogs (detecting them and detecting the availability of Pingbacks on their endpoints is another issue), if you do attempt to exploit any other system let us know the results. I’ll send you some files via e-mail in a minute, too.

Very interesting, I also came accross it from the coment at cloudflair, I would also be interested in your files, if possible.

Hi there

I would be very interested in your files as part of an ongoing research project. I hope to hear from you soon!

Regards,

Dexter

Check your e-mail for further details. Thanks for your interest.

Hi, I’m interested in the files used in this attack to see if I could look in to how to mitigate it. It seems like a really interesting attack vector. Even if I can’t do anything with it I’d still be interested in how it works. I’ve provided my email attached to this comment.

Hi there, thanks for this great article. I maintain several Drupal sites and occasionally participate the development. I am interested of testing this in my virtual network to see if this would be an issue for my clients. Could I see the files you used?

Thanks and keep me updated, please.

Is this still a problem?

If so, could I have the “files” so I can test different soloutions on the three wordpress sites that I am administrating?

Regards,

Andréas

Yep, vulnerability still exists, as far as whether it’s a problem or not depends on when it will start being exploited. Sent you an e-mail with some proof-of-concept files.

Hello soulseekah,

Its really interesting.

I am a undergraduate student from India working on Information Security.

Can you please mail me the required files, so that i can test in our lab discuss, and find out some solution.

Also suggest good readings if any.

Thanks in advance.. have a nice day.. 🙂

You’re welcome.

Hello,

Very interesting concept. I’m curious to see this work in a live (mock)environment. Can you send me the same associated files for testing?

Sent to your email. Enjoy.

[…] scenario where many wordpress sites could be asked to pull large files from a victim site, causing a bandwidth amplification attack on both the requesters and the responder. Additionally an extremely large number of wordpress sites […]

Hi, this issue seems very interesting for me to study in our closed environment. Could you send the PoC files to my email? Would be greatly appreciated. Thanks!

Enjoy.

Wow, this is a big reason for worrying, both for wordpress site owners and for anyone in general. I host a couple wordpress sites, for example.

Is disabling pingbacks the only real solution? isn’t it possible to somehow limit the ability of attackers to bring you down by checking for “suspicious” URLs or something?

Also could you mail me the files? I’m planning to do some testing.

Thanks for the great article and blog!

Files sent, thanks for your interest.

Hey I’m a security enthusiast that would enjoy taking a look at your PoC 🙂

Thanks!

Hooked you up with some stuff. Thanks for your interest.

[…] se explica mai in detaliu cum functioneaza atacul ddos https://codeseekah.com/2012/04/18/wordpress-dosnet Category(s): Anunțuri The Document Foundation a anunțat LibreOffice 4.0, suita office […]

Hey, I’ve been looking around for anything similar to this and am currently interesting how something like this could be done and than followed by securing it, seems interesting because I’ve never really heard of this yet it seems you can easily cause havoc with this and WordPress.com doesn’t even care. I was hoping if you could send me some code about how this would be done so I could study it myself and maybe find other big issues from it.

I think that this vector is not being used is because it’s probably cheaper and more efficient to use traditional botnets. Sent you some files over e-mail.

I would be interestd in this, could you please send me the files, as I have a wordpress site, and I know a few people with wordpress sites, so I would like to do some testing.

Also, why not put the files up publicy for download as you seem to be giving them away to everyone who asks? Is it because you don’t want to make it too readily available to hackers who just want to fos people?

Sent you an e-mail. I’m not putting these up for the reason you mention and to get a feeling for how interested the community is.

Can I get the PoC files as well? Great post.

Yep. Thanks.

I am sure we could force WordPress to establish a better way of handling pingback, if just enough users/developers put pressure ont hem.

Currently I am developing a fairly serious cms, and would love to see your work to figure out how I best can prevent getting attacked in this manner.

You got my email with this reply, hope to hear from you.

Jean

Done.

I’ve seen this floating around lately and one of my (old but still online blogs) were having a tonn of requests for that file.

Would you mind emailing me the scripts?

Thanks.

Not at all, check your mail.

Hi i do an article about exploits who have dramatic cost when you use a “magic cloud solution” , it seems that your script is one perfect example. (ddos or dramatic cost adjustement and no basic firewall could stop her)

Would you mind emailing me the scripts?

thx

Sent you an email. Enjoy.

Great post, thank you!

Could you please send me the scripts?

BR

Sent. Enjoy.

Hey, I came across this blog after reading about the recent ddos involving over 162,000 wordpress sites. This is a very interesting and crafty use of a legitimate “feature”. Would you be kind enough to send me your test code for review if you still have it? Thanks!

Sent you an e-mail with some stuff.

Hi soulseekah, could you email me the scripts as well? Thank you in advance!

Done.

Very interesting concept. I’m curious to see this work in a live (mock)environment. Can you send me the same associated files for testing?

The latest version of WordPress have limitations in this regard, rendering the attack less effective, but I’m sending you the old files.