Why WordPress Authentication Unique Keys and Salts Are Important

…or how to forge authentication cookies in WordPress

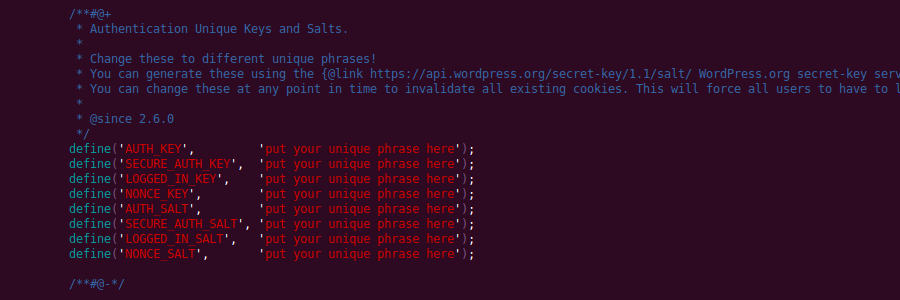

If you’ve ever installed or setup WordPress you should have surely seen your wp-config.php file, which contains the necessary configuration directives in order for WordPress to work. One section of the configuration file is dedicated to authentication keys and salts and this article will show you why you should keeps these safe and unique, regenerate these once in a while.

Salt, salt, salt… care to pass me the salt? Don’t! If I know your salt there’s a good chance I’ll be inside your WordPress administration panel within a week. Why? Because WordPress depends on the safety of these salts, once they are compromised the security behind authentication is relatively weak. But how?

If you don’t know or don’t remember what cryptographic salt is, feel free to brush up. The notion of a cryptographic hash function should also be familiar to you in order to better enjoy and understand this article.

So let’s get going. WordPress does not use PHP sessions to keep track of things like login state, it uses bare cookies. This means that much of the state information is stored on the client-side inside of these cookies. And client-side means that the “client” gets to play around a bit.

The authentication cookie, the name of which is stored inside of AUTH_COOKIE, which is formed by concatenating “wordpress_” with the md5 sum of the siteurl (default-constants.php#L142). This is the default behavior and can be overridden from inside your configuration file, by setting up some of the constants upfront.

The authentication cookie for this website (at the time of writing) is wordpress_7a3d03248fc2e614fc5e4b5aa9c560ed, with siteurl being “https://codeseekah.com”. That was easy and never meant to be hard.

The authentication cookie value is where the difficulty lies, obviously. The value is a concatenation of the username, a timestamp until which the authentication cookie is valid (can be any value in the future really), and an HMAC, which is sort of a key-biased hash for those who pulled of a TL;DR right now. The three variables are concatenated with the pipe character |.

username|timestamp|hmac

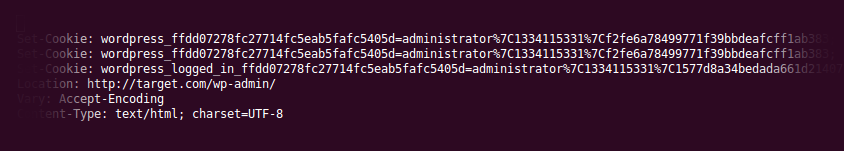

administrator|1334115331|f2fe6a78499771f39bbdeafcff1ab383

But wait, wouldn’t this cookie be constant, valid until the timestamp expires if all login credentials remain the same?

It certainly would. Morever, it is constant for a particular login, timestamp and set of keys. Authentication cookies cannot be destroyed until they expire. If an attacker gets their hands on a user cookie that has its expiration timestamp value set to 10 years in the future, as long as a subset of authentication keys and salts remain the same along with the password, they can attain login state without a password whenever they like for years to come.

So how would an attacker reconstruct this 128-bit HMAC in the cookie?

Lo and behold the default routine. Here’s how the HMAC is constructed:

$hash = hash_hmac('md5', $username . '|' . $expiration, wp_hash($username . substr($user->user_pass, 8, 4) . '|' . $expiration, $scheme));

We know the username (finding out WordPress usernames, and the verification thereof, is out of the scope of this article; but stay tuned, I’ll write a little something on timing attacks for username validation in WordPress later this week or early next week), we know the scheme is auth or secure_auth based on whether WordPress is in SSL mode at the time of the attack, expiration is any valid UNIX timestamp that is in the future, and given the knowledge of the necessary key and salt (AUTH_KEY and AUTH_SALT) the defined wp_hash and wp_salt functions are both predictable.

What this leaves us with is a mere 16,777,216 combinations to try and guess a mere 4 characters of the user’s password hash in the following 64-character keyspace: ./0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz (as defined by PHPass).

Bruteforcing is relatively effortless. Send HEAD or GET requests to wp-login.php with the cookie and look for a 302 response code (this page redirects logged in users to the index of wp-admin, meaning we’re in). To generate less suspicion in server logs other pages, including ones on the front-end can be checked against (the Admin bar, Logout, edit links, etc.). An attacker with a single machine that does around 30 request per second can exhaust all the possibilities in a week (as long as the server can keep up), no CAPTCHAs, fancy login routines, nonces, pure lightweight bruteforcing. You’ll have to be a worthy target, though, no casual bot sweep will ever exploit this. So I wouldn’t panic.

Now you can see why I said it was relatively easy, since bruteforcing a 128-bit hash (HMAC MD5) would require up to 3.4*10^38 tries (the hash bits themselves, not the input). Bruteforce that! However, knowing the keys reduces that number of possible hashes by 2*10^31 times. Yes it’s 200,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times easier to forge the WordPress authentication cookie if you know the keys.

Once you’re in, WordPress will greet you with some extra cookies that you get to keep as well.

Attaining the authentication keys themselves is outside of the scope of this article, there are dozens of attack vectors, including social engineering, since the keys look just a bunch of crap and nowhere does it say that you shouldn’t share them with anyone. Tweet me yours, the Internet is all about sharing :D.

Mitigation

Protecting yourself is quite easy.

- Pick strong unique keys, just like passwords, but the benefit of it all is that you don’t have to remember them. Always set them in you configuration file.

- Change keys every now and then. One of the WordPress.org APIs generates authentication keys and salts and you’re free to use it. It doesn’t take more than a minute to change these via copy and paste. All compromised cookies are suddenly invalidated.

- Do not let go of the keys, nobody will ask you for these keys, there are of absolutely no external value.

- Set the

COOKIEHASHvalue to something less predicatable in your configuration file, that way the name of the cookie itself will pose a problem to attackers. - Increase entropy, explained below.

- Keep your server safe, patched, etc. common sense approach to protecting your files, WordPress and the server.

Increasing entropy

Increasing entropy from 16,777,216 possible HMAC hashes is fun and easy. All the functions are pluggable. Plug the wp_hash function and add something unpredictable:

function wp_hash($data, $scheme = 'auth') {

$salt = wp_salt($scheme) . 'PREDICT THIS, BRO!';

return hash_hmac('md5', $data, $salt);

}

Ouch, suddenly there is 128-bits of entropy, given that your function is invisible to the outside world. That string can come from anywhere else (think remote, database, request variables). Make sure you know what you’re doing though, hashes are generated for many things inside WordPress so the above code will probably mess things up.

I wouldn’t expect the WordPress development team to increase entropy out of the box for us WordPress fanatics, even if it would take a 1-character change in two functions to increase the length of the user password hash fragment from 4 characters to say 5, which increases the number of tries up to 1,073,741,824, which will take 30 days at 60 tries per second non-stop, making the authentication cookie forging attack vector less attractive.

Unless your WordPress dashboard provides direct communication with a nuclear C&C center I wound’t worry about this all anyway. There are million and one and other ways to get in, which brings be to the…

…Conclusion

Stay safe. Over and out. 🙂

Thanks for a yet another great post! Keep up the good work!

I have one question though: won’t users password fail if I update the api-keys?

Thanks for dropping by, Tobias. Great question. The standard

wp_check_passwordfunction in pluggable.php calls on PHPass to decode the hash. In PHPass the salt for the password hash is stored in the hash itself, check out https://core.trac.wordpress.org/browser/tags/3.3.1/wp-includes/class-phpass.php#L111 for insight into how this happens. So in short, PHPass does not use the wp-config.php authentication keys and salts to hash passwords, that is why it’s absolutely safe to change these anytime, unless they are being used by plugged password hashing routines.Ah, thank you for the input. Will try it on some old wp installs right away. You never know..:)

I landed here after reading tentblogger’s how-to salt-key post, then looking for additional articles. Thank you for the link to the salt key and hash explanation which greatly helped to make sense of salt. Your post is beyond me right now but I read it all anyways. I am about to set-up my very first WordPress site and want it to be off to a good start.

My point of writing? A plugin,if possible, please.

This is what crossed my mind after reading your post…

After recently having had my computer wiped out by a nasty virus that also corrupted my backups despite all sorts of protection, I am more interested than ever before in avoiding similar pains.

Now that you have mentioned changing salt keys often (which I will do), obfuscating the COOKIEHASH and also increasing entropy which I would not attempt, I am wondering if is it possible to create a WordPress plug-in that can implement these changes for others like me?

I would like such a plugin to change these three aspects frequently but in a non-linear fashion, for example, on random days. Perhaps this plug-in can also have password access to use it?

I think this salt security plugin would be an essential for anyone concerned about their site security. What might take one person 10 minutes to set-up may take weeks for another who is less adept.

I don’t think one’s site has to be anything important because it might be hacked by someone simply bored with life or perhaps someone picking on small fish to practice for a larger goal.

As an aside, I have been also looking for a way to offer an expiring temporary admin access to others that help with code or other structural issues. I do not want to give out the admin access info. I wish WordPress would implement that option or maybe it exists and I haven’t stumbled upon it yet.

Thank you.

Thank you for stopping by, Pamela. The probability of this attack vector being used on a site is close to none, those simple bored will not use this technique since it’s very difficult to mount. The attacker would have to have your hashes (i.e. access to wp-config.php probably, don’t keep a wp-config.php.bak lying around), which is in itself difficult. Guess a username (remove the “admin” account), and spend weeks trying to force their way into the administrator’s panel by forging WordPress authentication cookies. There’s no need to be too concerned as much more efficient ways of getting in exist. Change your passwords frequently (this will change the authentication cookie), always update, watch out for plugins and fancy themes with holes in them (plenty of those around), setup a strong server configuration (including logging and alerts) and you should have nothing to worry about. Good luck!

And as for temporary admin access – just create a new administrator user and change passwords after work is done via the account. Any plugin is usually too much overhead.

Thank you for this advice.

It would be nice if someone with considerable experience wrote a comprehensive step-by-step tutorial on what one ought to do. Changing admin access and passwords in a wise and unique fashion would be a useful article as well.

Articles are plenty but few have your obvious expertise.

WordPress may be simple but there is a lot to learn about it if one is to use it correctly. The Codex is a huge help. I looked over the “Editing_wp-config.php” article in the WP Codex and read that salt keys are now enabled by default.

You wrote “There’s no need to be too concerned as much more efficient ways of getting in exist.”

I look forward to your next post regarding this topic. It will be too technical for me, however you certainly are most generous with details so I know that whatever information I glean for it will be helpful.

Do you offer your services to examine sites for security flaws and make changes/recommendations?

Pamela, hardening WordPress has been written about hundreds of times. A good start would be to read the Hardening WordPress Codex page which offers a lot of sound advice on how to manage most of the security aspects of WordPress and the environment it resides in. There is never a 100% guarantee of security, if they want to get it – they will.

There are many interesting solutions that offer advanced layers of protection, like one-time passwords (there’s a WordPress plugin for that, too) which works great against keyloggers and network sniffing to some extent as the attacker never knows the next password (yet, by stealing Cookies he should be able to share a session with you while you’re logged in). Activity monitoring and SMS/e-mail alerts are great, too.

But again, a website that holds no value other than spam and black-hat SEO, or server resources takeover, a strong password, an updated WordPress with secure plugins and themes, and a secure server should never raise any concerns. And always keep backups (reminds me of needing to backup this blog). WordPress itself is seldom the weakest link in the chain – badly-written plugins and themes are.

Hope this helps. Will contact you via e-mail in regards to security auditing and consulting.

Hello! This is great work! But I’m really confused about something. Consider I know the contents of wp-config.php(keys, salts).

I have all the needed variables to compute $hash, except $user->user_pass.

The user’s password hash in unknown to me, but to compute $hash I only need 4 characters from the password’s hash. As I don’t know this password hash, I must generate all the possible combinations of 4 character length from the keyspace “./0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz”. For each combination, I generate a $hash, then try it against the target.

Is this correct? Thanks!

That is absolutely correct. If you know the salts, you only need to bruteforce 4 hash characters to eventually generate a valid WordPress login cookie for that user.

[…] We won’t go into the technical details of authentication keys and salts but if you’d like a more technical explanation then this article is a good one: https://codeseekah.com/2012/04/09/why-wordpress-authentication-unique-keys-and-salts-are-important/ […]

[…] 1) Keys and Salts – Once one knows them, they can take advantage of that to get into the Dashboard. Click here to read more about this! […]

[…] highly recommend reading Why WordPress Authentication Unique Keys and Salts Are Important – it is a great read. As the article mentions, changing your keys and salts now and again is […]

[…] course, leaked salts were a HUGE problem of their own, and an adversary with salty hands ???? in older versions of WordPress will probably go straight […]

[…] that hoopla all about, you can find out more about here, but, in short, they are meant for encrypting cookies that your WordPress site stores on your […]

[…] fact, according to a WordPress code expert, it’s 200,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times easier to hack into the WordPress […]

[…] Why WordPress Authentication Unique Keys and Salts Are Important […]

[…] Why WordPress Authentication Unique Keys and Salts Are Important – …or how to forge authentication cookies in WordPress […]

[…] but in 2017 we still see plenty of WordPress sites that aren’t using salts to encrypt cookies. This blog post goes into a ton of technical detail about why that matters, but for the purposes of this article, […]

[…] highly recommend reading Why WordPress Authentication Unique Keys and Salts Are Important – it is a great read. As the article mentions, changing your keys and salts now and again is […]

I am looking at a site with wp-config exposed and have the salts and keys but I am struggling to implement this brute force method. Could you provide any more detail on how I would construct these GET, HEAD requests? Specifically with generating the HMAC’s to test from the exposed SALTS and KEYS.

Kyle, I suggest you open the latest source (things have changed a bit since this was written, but not too much) code and study it to better understand the mechanisms involved and what it is that you’re trying to achieve. On its own just getting the keys is not vulnerable. The vulnerability comes when plugins use nonces for security (see WordPress Nonces Vulnerabilities) among other things.